The so-called Little Mosque on the Tundra sits two degrees beyond the Arctic Circle in the town of Inuvik, Northwest Territories. There, in the far north of Canada’s Far North, the mosque serves a small but thriving community of Arabic-speaking Muslims. Why these hardy immigrants chose this town, of all places, to make their home in Canada, is somewhat of a mystery (it is so far north and west that the direction of prayer to Mecca is through the North Pole!). As a country of immigrants, we have come to expect the cacophony of foreign tongues heard in the diverse neighbourhoods of Toronto or Vancouver. But as it turns out, Inuvik is just one of Canada’s many surprising, and oftentimes isolated, linguistic outposts.

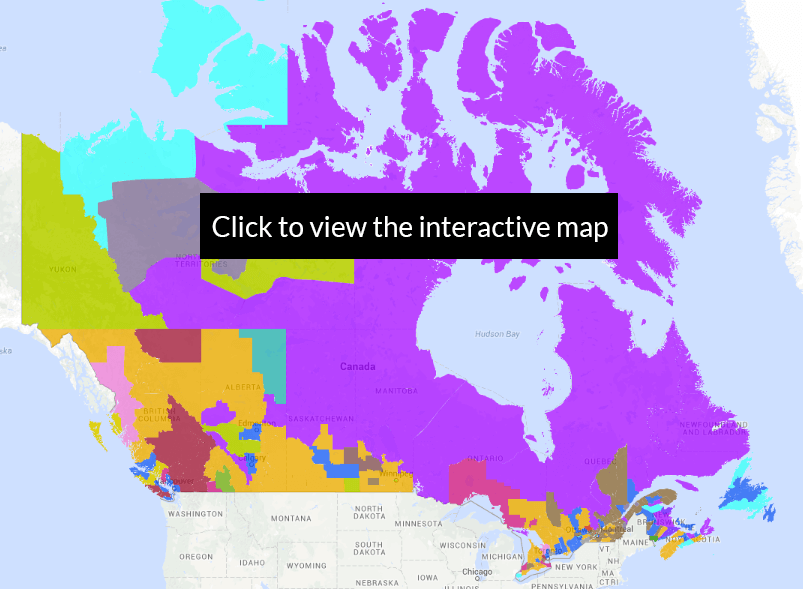

To explore this phenomenon, we created an interactive map that displays which language besides English and French is most prevalent in different parts of the country. We divided the country into census divisions, and determined the popularity of a language by the number of residents in that division that primarily speak it at home (based on data from the 2011 census). There are certainly many interesting trends apparent in this map, but below we highlight a few of what are perhaps the most unexpected.

Yiddish in Quebec

Quebec has long had a thriving Jewish community (think names like Mordecai Richler, Leonard Cohen, Naomi Klein), and this group is generally thought of as part of Quebec’s anglophone community. However, many Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe originally came speaking Yiddish, and though this rich and historical language is slowly marching toward critically endangered status, there remains a modest Yiddish-speaking community in and around Montreal, composed primarily of Hassidic Jews, and to a lesser extent, young hipsters trying to reconnect with the language of their ancestors. We’ll have to see in 10 years how this language — that is no longer really native to anywhere — is holding up in Quebec.

Gujarati in Northern Alberta

Fort McMurray is a long way from Gandhinagar, the capital of Gujarat state in India. Actually, Fort McMurray is far from just about anywhere. But as it turns out, several hundred Gujarati families have settled in this northern Alberta city, attracted by plentiful jobs in the booming oil and forestry sector. While Punjabi speakers dominate the British Columbia linguistic landscape, and Urdu has gained steam in the Greater Toronto Area, Gujarati — only the 7th most commonly spoken language in all of India — has taken hold in this unlikeliest of Canadian places.

Filipino in the Yukon

With its booming economy, driven primarily by mining, the Yukon has attracted a surprising wave of immigrants from the Philippines, who are more used to tropical heat and hurricanes than frozen winters and the midnight sun. Word seems to have gone around about the Yukon’s aggressive Nominee Program for new immigrants, so much so that now the Filipino-speaking population, based primarily in Whitehorse, comprises the largest non-English speaking language group in the entire territory.

Punjabi in BC

You know an immigrant group has “made it” when Hockey Night in Canada creates a special version of the show in its native tongue. So it is with Canadian Sikhs, whose dominant language Punjabi has become the most common South Asian language in Canada, and in particular in British Columbia. Outside of Vancouver and Victoria, where Chinese reigns among immigrants, Punjabi strongholds stretch from the south of the province near Abbotsford and The Okanagan all the way up to the isolated Northern Rockies. The famous Gur Sikh Temple in Abbotsford, built in 1911 by turn-of-the-century Sikh pioneers, is a testament to the community’s deep roots in the province.

Korean in New Brunswick

When you think “Koreatown” in Canada, you usually think of that famous stretch of Bloor Street in downtown Toronto, between Bathurst and Christie, with its delightful restaurants serving all manner of bibimbap and kalbi and kimchi, and plentiful karaoke bars blasting K-Pop. Over 50,000 Korean Canadians have settled in Toronto. But as it turns out, Moncton, New Brunswick has long been making its own push to grow its Little Seoul, advertising its churches, community centres and Korean-owned business to woo Korean immigrants to its already impressive 400-family community. Recently, however, New Brunswick’s Korean-Canadians have been feeling the economic pressure, and are starting to trickle back to Canada’s biggest cities.

Spanish in Quebec

Montreal is becoming ground zero for Canada’s new bilingualism, where residents increasingly speak just one of the country’s two official languages plus an additional immigrant language. In greater Montreal, over 600,000 people speak a language besides English or French as their mother tongue, with Arabic and Spanish leading the charge. When restricting to the language most often spoken at home, Spanish ekes out a small lead in the city of Montreal, as well as in many other Quebec cities including Drummondville, Sherbrooke, Lac-Mégantic, Shawinigan, Trois Rivières and Quebec City. This large influx of allophones (immigrants who speak neither English nor French) is causing some angst among politicians in Quebec, who are concerned that the French language is being further diluted by the new class of multicultural arrivals.

Aboriginal Languages in the North. And the Centre. And the East.

What is perhaps most surprising is the dazzling strength and diversity of Aboriginal languages in so many regions of Canada (Aboriginal languages refer to Inuit, Métis and all First Nations tongues). Cree, with almost 120,000 native speakers, appears in our map as one of the most dominant Aboriginal languages, with truly national reach: it stretches from the west in Alberta all the way to the east in Quebec (with smaller pockets of speakers in other areas too). More regional Aboriginal languages abound: in the north is Inuktitut, the principal language of the Inuit in Northwest Territories and Nunavut, along with Dene (sometimes referred to as Athabascan). Ojibway is dominant in Manitoba and northern Ontario, Innu in northern Quebec and Labrador, Atikamekw in southwestern Quebec, and Mi’kmaq in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Stoney (or Nakoda), a language spoken by just over 3000 people, is dominant in a small area of western Alberta that includes Banff, but like many small indigenous languages, is now struggling to stay alive, with so few children learning it as their native tongue.

Follow us on Facebook or Twitter to learn about our latest maps, stories and analysis!

Methodology Notes

What does “Chinese” refer to in our map? Statistics Canada permits responders to indicate both a specific dialect of Chinese (e.g. Cantonese, Mandarin, Shanghainese, Hakka, etc.) as well as a generic “Chinese” response. See an example data table here. Since a very large proportion of respondents simply choose “Chinese,” there is no way of knowing which dialect is most common in any particular region. As such, we decided to combine all Chinese dialects plus the generic “Chinese” into a single category.

Why do Aboriginal languages all appear as one colour? We thought about this a lot when creating the map, and the primary reason is that there are simply not enough colours in the visual spectrum to use a distinct colour (and texture) for each language so that the map is actually visually pleasing and comprehensible. The editorial decision was made to combine the Aboriginal languages into a single colour (while retaining the distinctions and language-specific details when hovering). Why do we think this was a good decision? Almost all of the feedback we’ve received has been “Wow, I’m so happy there’s so much purple, it’s so great how much of Canada is dominated by indigenous languages!”. The purple wave is so striking, so visually stunning, and it clearly communicates the strength of the Aboriginal population across much of Canada — this effect would have been lost if we had selected different colours, and it would look just like everyone else. So we believe we struck a good balance.