UPDATE: Check out our 2018 ranking of the most miserable sports cities!

Of the many notable sports storylines from the past year, perhaps the most remarkable is just how many lengthy playoff and championship droughts were busted. At long last, miserable fans across the continent — except of course, in Cleveland — were rewarded for their years of fruitless, unfulfilled loyalty.

Fans in Oakland celebrated as the Golden State Warriors, long a sad sack franchise, put an emphatic and splashy end to their three decades without a championship. In Houston, both the Rockets and Astros broke long streaks of post-season futility with modest but exciting playoff runs. And one quick glance at the four MLB teams left standing in late October made it clear that some hard-luck fans would finally be leaving their misery behind: there were the Chicago Cubs, who famously hadn’t won a World Series since the waning days of the Ottoman Empire; the New York Mets and Kansas City Royals, who each hadn’t smelled a World Series since the mid-80s; and the Toronto Blue Jays, who had just broken the longest playoff drought (22 years) across any of the major pro sports leagues.

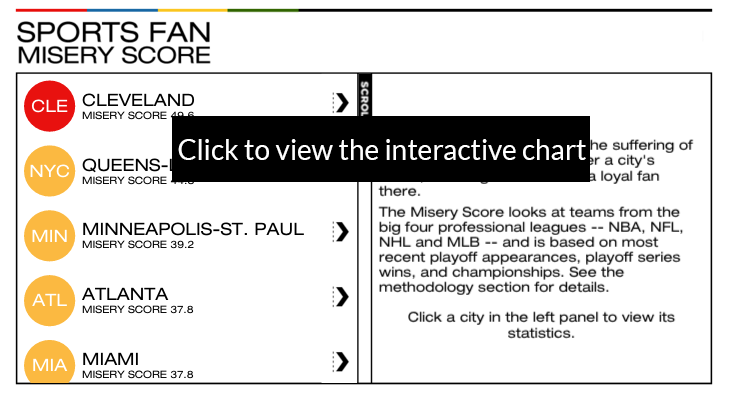

Whereas last year’s inaugural misery rankings celebrated a small collection of long-suffering, woebegone sports cities, this year’s rankings reflect a world where there remains one overwhelmingly hard-luck town (Cleveland!), and a host of cities that have started nibbling on the edges of success, but still crave that ever elusive championship. Like last year, we considered those cities in the US and Canada with at least three teams in the four major professional leagues. We weighed playoff appearances, playoff series wins, and championships in the Misery Score. We also relied heavily on recent success, since there’s no better way to forget a drought than with a lot of winning (we’re looking at you, Boston). See the Appendix for details on our scoring system and clustering choices.

1. Cleveland (No change)

In last year’s misery rankings, we documented the many heartbreaking disasters in Cleveland’s painful sports history, from The Shot, to The Drive and The Fumble. (The pain of The Decision may have since melted away, however.) Since then, well, not much has changed. The Browns are still terrible. The Indians’ outlook is mixed, with some predicting a breakout season and others a bit more hesitant. And while the Cavaliers have LeBron (and Kevin and Kyrie), it’s tough to imagine the team winning a championship with the Warriors and Spurs looking on from the Western Conference, not to mention the Raptors nipping at their heels in the East.

It looks like Cleveland’s championship drought, which started way back in 1964, will haunt the city for a little while longer.

2. Queens and Long Island (Last year – 3rd)

All things considered, it was actually a pretty decent year for fans of New York’s less flashy, so-called “little-brother” teams, each with historical roots in Queens and Long Island. The Mets, led by an ace pitching staff that includes Jacob deGrom, Matt Harvey and Noah Syndergaard, stormed through the playoffs but were ultimately humbled by the Royals in the World Series. The New York Islanders, who are now based in Brooklyn but still have a passionate following in their original home on Long Island, are starting to look like a functional hockey organization again, though they haven’t won a playoffs series since 1993. The Jets, whose first home in Queens remains their cradle of support, have moved on from the tumultuous Rex Ryan era and are looking optimistically to the future. Last season’s winning record was a sign of potential things to come.

Ultimately, however, it’s all about championships. And the fans of New York’s oft-forgotten teams have now been waiting for 30 years, second in futility only to Cleveland among major sports towns.

3. Minneapolis-St. Paul (Last year – 5th)

Another ho-hum year for sports in the Twin Cities, and another year without a championship for these success-starved fans. Sure, the Minnesota Wild have figured out ways to squeak into the playoffs here and there, and sometimes even win a series. And the Vikings even occasionally dip their feet into postseason waters, only to quickly bow out. In basketball, despite the presence of an exciting young superstar like Andrew Wiggins and the return of prodigal son Kevin Garnett, the Timberwolves will be lucky to reach anything resembling success in the Western Conference within the decade. Believe it or not, the Twins won Minneapolis-St. Paul’s most recent championship…in 1991. Don’t expect them to win the next one.

4. Atlanta (Last year – 6th)

Atlanta is a newcomer to our top 5, and it’s another city in our list where the misery of sports fans comes not from wretched, basement-dwelling teams, but rather from the insidious feeling that a championship parade down Peachtree Street is unlikely to happen again for some time. The Falcons, year after year, are just so-so. Same with the Hawks. And the Braves, who last gave the city’s tomahawk-chopping fans a championship back in 1995, are probably the worst of the bunch.

5. Miami (Last year – 8th)

Miami probably represents our most controversial pick in this year’s rankings, but the math doesn’t lie, so bear with us as we explain. First, there are the city’s relatively less popular teams, the MLB’s Marlins and NHL’s Panthers. The Marlins haven’t made the playoffs since 2003, and they’re just bad. The Panthers haven’t won a playoff series in twenty years, and while this year they’ve managed to put together a solid playoff-worthy record, there is no expectation that 44-year old Jaromir Jagr will lead them anywhere near Lord Stanley’s Cup.

Looking next at the city’s more glamorous teams, we see further reason to worry: the Dolphins haven’t won a championship since the Nixon administration, and haven’t even been in the playoffs since 2008. And yes, the Miami Heat did win a championship a mere three years ago. We know that’s a big deal and should count for something. But consider that in the intervening years, LeBron James has taken his talents back out of South Beach, while the remaining members of the Big 3 (Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh) are well into their 30s and are suffering from an alarming array of health problems. Sorry, Miami fans, but we think you’re going to be miserable for a while longer.

Which city do you think deserves to be in the top 5? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter and join the discussion.

Methodology Notes

Cities with Multiple Teams

Several large cities in North America have more than one professional team in the same league. To handle these cases, we divided fans up into natural allegiances, and calculated separate misery scores for each set of fans. Chicago is an easy one: one set of fans supports the Cubs (Chicago A), while the other supports the White Sox (Chicago B). Los Angeles is similar, with those supporting the Clippers (Los Angeles A) and those supporting the Lakers (Los Angeles B). Anaheim-based teams the Angels and the Ducks are not included due to geography, and since their fan bases are not as readily associated with the set of LA teams.

The San Francisco Bay Area has two football teams and two baseball teams (and a single basketball and hockey team). Those in the East Bay typically back the Raiders and Athletics (San Francisco Bay Area A), and those in SF and the peninsula back the 49ers and Giants (San Francisco Bay Area B).

Finally, there is the complexity of New York City. There are of course many exceptions to the clustering that we selected, but generally speaking, we have the “big brother” and “little brother” teams of New York. The Rangers and Knicks (who both play in Madison Square Gardens), along with the Yankees and Giants, have a somewhat consistent fan base. Similarly, the Jets and Mets (who shared Shea Stadium in Queens), along with the New York Islanders (who are originally from neighboring Long Island), tend to share fans based on geography and a common history (Queens-Long Island). We omitted from our analysis the New Jersey Devils, as well as the Brooklyn Nets (who may still be finding a consistent fan base after moving from New Jersey).

The Misery Score Explained

We first compute a misery score for each team, as follows: a team gets a demerit point for each year since (i) it last made the playoffs, (ii) it last won a playoff series (which doesn’t include MLB play-in game wins), and (iii) it last won a championship. We cap each of the three above point values at 30, because the average fan’s age in the major sports is approximately between 42 and 43, and the age of 12 or 13 is the general age of enlightenment when fans start to really understand sports (and the misery that comes with losing). These points are added together, which gives each team a number of points between 0 (if the team won a championship last season) and 90 (if the team hasn’t made the playoffs in the past 30 years); we then normalize these values onto the [0,100] scale, to get a team-level misery score.

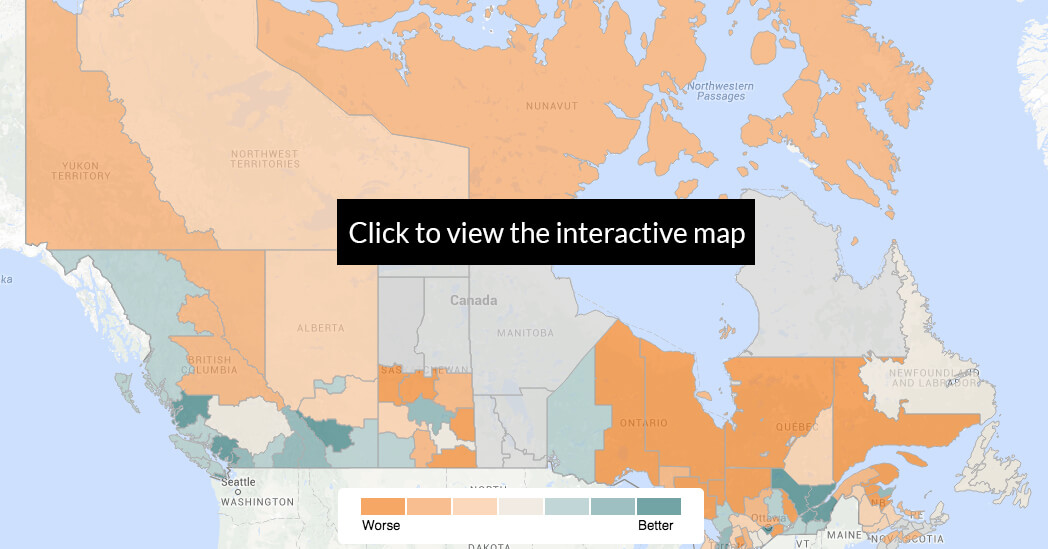

Finally, for each city, we take a simple average of its component teams’ misery scores, to get an overall city-level misery score. For ease of interpretability, we bucket these city scores into 4 categories: green (0-15), yellow (15-30), orange (30-45) and red (45+). Green means that you only need to look back, on average, about 5 years to see a lot of success (Boston); yellow look back 10 years (Tampa Bay), orange look back 15 years (Washington, Philadelphia and Phoenix), and red over 15 years (Cleveland).

Note that we have only chosen to display NFL champions since the first Super Bowl (in 1967). Teams with their last win prior to that (ex. Detroit) are marked as “NA” in our graphic.